Dear colleagues and friends,

A colleague who has always been intrigued by the origins of life on Earth shares this article written by Arianna Soldati, published on May 31, 2024 in the news (press releases) section of the Geological Society of America website and translated by us for this space. Let's see what we learn here...

Stromatolites are the oldest geological record of life on Earth. These curious biotic structures are made up of algae carpets that grow toward the light and precipitate carbonates. After their first appearance 3.48 Ga (Gigaños: 1 billion years) ago, stromatolites dominated the planet as the only living carbonate factory for nearly three billion years.

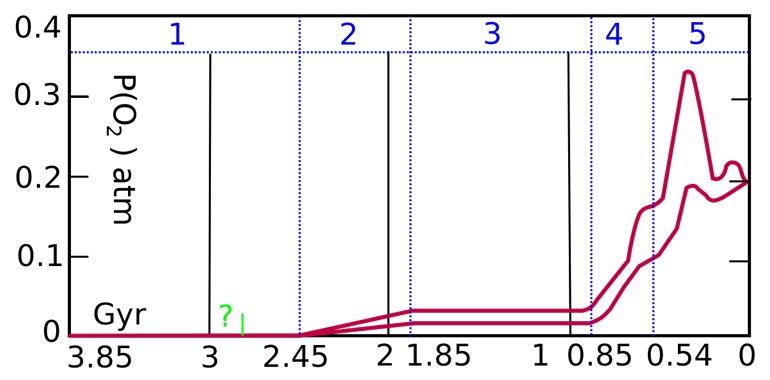

Stromatolites are also partially responsible for the Great Oxygenation Event, which dramatically changed the composition of our atmosphere by introducing oxygen. That oxygen initially eliminated competition from stromatolites, allowing their prominence in the Archaic and Early Proterozoic environments. However, as more life forms adapted their metabolism to an oxygenated atmosphere, stromatolites began to decline, appearing in the geological record only after mass extinctions or in difficult environments.

“Bacteria are always present, but they don't normally have the opportunity to produce stromatolites,” explains Volker Vahrenkamp, author of a new study in Geology. “They are greatly outnumbered by corals.”

In modern times, stromatolites are relegated to extreme environments, such as hypersaline marine environments (for example, Shark Bay, Australia) and alkaline lakes. Until recently, the only known modern analog of the biologically diverse open and shallow marine environments where most proterozoic stromatolites developed was found on the Exuma Islands in the Bahamas.

That is, until Vahrenkamp discovered living stromatolites on Sheybarah Island, on the northeastern shelf of the Red Sea in Saudi Arabia. Vahrenkamp was studying tipis structures (salt crust domes that can be seen from space) when he came across the modest field of stromatolites. The discovery was surprising, but thankfully, Vahrenkamp is one of the few people to have seen stromatolites previously in the Bahamas.

“When I stepped on them, I knew what they were,” Vahrenkamp explains.

“It's 2,000 kilometers of carbonated shelf coastline, so in principle it's a desirable area to search for stromatolites... but it's the same in the Bahamas, and yet there's only a small area where they can be found.”

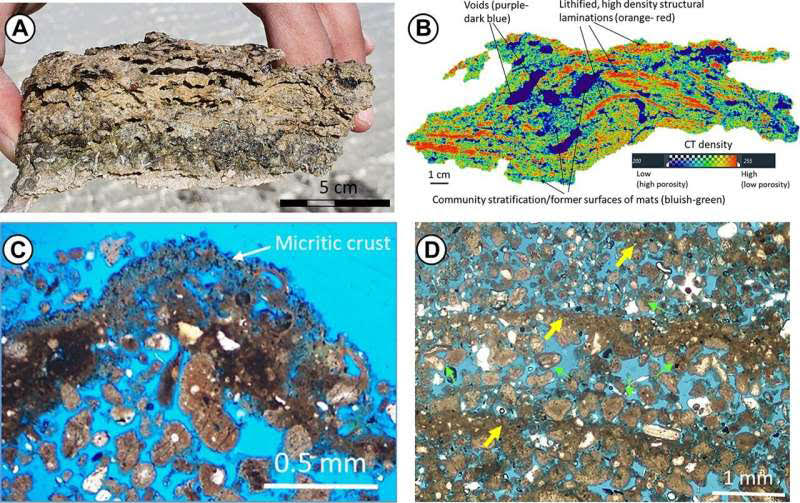

Sheybarah Island is a shallow intertidal and subtidal environment, with regularly alternating humidity and drought conditions, extreme temperature oscillations between 8°C and >48°C and oligotrophic conditions, much like the Bahamas. Since similar environmental conditions are widespread throughout the Al Wajh carbonate platform, there could be other stromatolite fields nearby. Vahrenkamp and his team have started this exploration work, but the stromatolites are small, about 15 cm in diameter, and are therefore difficult to detect until you get very close.

There are several hundred stromatolites in the Sheybarah Island field. Some are examples of perfect, well-developed textbooks. Others are more laminar, with low relief. “Maybe they could be juveniles,” Vahrenkamp hypothesizes, “but we don't know what a baby stromatolite looks like. They should start small, but we don't know.”

Part of the problem is that we don't know how fast stromatolites grow. Dating them is very difficult, because they contain two different carbonate components that are practically impossible to separate: the one freshly precipitated by microbes, which is of interest, and the carbonate sand present in the environment, which is misleading. Currently, the Vahrenkamp team monitors the field monthly to record any visual changes. Soon there could be an attempt to transfer some stromatolites from Sheybarah Island to an aquarium and cultivate them there: an exciting experimental perspective.

The discovery of Vahrenkamp provides us with an opportunity to better understand the formation and growth of stromatolites. This will provide information about early life and the evolution of the oceans on Earth and may even help us in the search for life on other planets such as Mars. What would life be like on Mars and how would we recognize it? Observing stromatolites, which were the first forms of life on Earth, before our planet even had an oxygenated atmosphere, is a very promising avenue.